Complicated guy, Paul Gauguin, both in life and in art history. The painter of the mango-and-orchid palette was a romantic outsider who sacrificed all for personal freedom and art. He was also, we have come to learn, a bully, a liar and a sexual predator, who staged his fabled Tahitian idyll to generate fame.

Upon arrival on the island in 1891 (his wife and five children long since deserted), Gauguin milked his colonial privilege for all it was worth, bedding local teenagers, some of whom he painted, and having islanders cater to his material needs. This view of Gauguin as creep surfaced with the rise of identity politics and post-colonial studies in the 1980s. In the #MeToo era he seems ripe for shaming into oblivion, yet he’s more visible than ever, in museum shows and now in three solid, cautiously unsensationalised books.

Of the three, The Gauguin Atlas, by Nienke Denekamp, is both the least critical and the least focused on his art. Framed as a sort of career Baedeker, it narrates his life in a series of brief chapters organised by his oft-changing places of residence.

A year after his birth in Paris in 1848, his father, a dissident writer fleeing Napoleon III’s wrath, moved the family to South America. He spent his first six years in Lima, Peru, where the seeds of his later self-image as a cultural alien seem to have been planted: Although his relatives in that country were Spanish colonials, he would falsely claim to be of Incan descent.

As an antsy adolescent, he joined the French merchant navy and sailed as far as India. In his 20s, back in Paris, he married and settled into a bourgeois track with a job in the stock market. He also began to collect and make art. When the stock market tanked in 1882, he gave up the semblance of normality to become a full-time artist, wanderer and freeloader.

The Gauguin Atlas follows his travels, year by year, to London, Brittany, Panama, Martinique, Tahiti and finally the Marquesas Islands, where he died at 54. The book contextualises its chronicle of whom he met and what he did within the cultural moment. Most of the illustrations are from historical archives; relatively few are of Gauguin’s art. This facts-only approach makes for a propulsive read, but doesn’t allow for much in the way of aesthetic, social or psychological analysis.

Savage Tales reproduced by Linda Goddard

The other two books, by contrast, take his output as their primary focus. They view him through it. There’s quite a bit of work reproduced in Linda Goddard’s Savage Tales, though mostly of a kind we seldom see in museums: his illustrated journals, political satires and books.

His one well-known book, Noa-Noa (1894-1901), is ostensibly an autobiographical account of his first two years in Tahiti. But many scholars, including Goddard, take it as an exercise in fact-based fiction, intended to advertise, for a Parisian art clientele, the artist’s conversion from repressed European to noble wild man.

Savage Tales approaches Gauguin’s extraordinary journals in the same light. With texts and images lifted from Western ethnographic studies and interspersed with annotations and drawings, they functioned as prompt books for the vaunted transformation. Taken together, the writings form an episodic account of a complex persona under construction, the public face of a man who was at once a ruthless opportunist and a creative misfit.

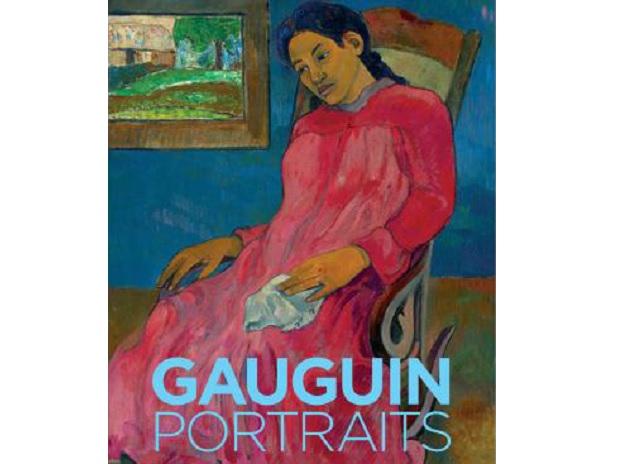

Gauguin: Portraits, the catalogue for a major exhibition that originated at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa

Goddard also contributes a balanced essay, neither prosecutorial nor fully forgiving, to Gauguin: Portraits, the catalogue for a major exhibition that originated at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Of the three, this book is by far the most visually luxurious. Its large-format reproductions of paintings and sculptures are a persuasive reminder — those colours! — of what made Gauguin the modernist pioneer he was, and the contemporary star he is.

By concentrating on a single genre, the book traces the curve of his career, from his influences (his early teacher, Camille Pissarro, his peer Vincent van Gogh) to those he influenced (among them Pierre Bonnard and Félix Vallotton). Not all of the works herein are first rank, but all are vital components of a performance of self-invention, especially Gauguin’s self-depictions as variously light and dark-skinned, and a “series of personae and alter egos” that included dreamboat, monster, mortality-stunned elder and, in one case, unabashedly, as a suffering Jesus Christ.

The catalogue’s good, very readable essays all touch on the ethical reservations that are now forever attached to his body of work. At the same time the reproductions stand as proof that at least some of his art is still, more than a century on, stop-and-stare beautiful, and in ways that no other art is.

© 2019 The New York Times

First Published: Sat, November 23 2019. 01:24 IST

read the full story about We’re still talking about Gauguin

#theheadlines #breakingnews #headlinenews #newstoday #latestnews #aajtak #ndtv #timesofindia #indiannews